I think it’s time we get a little personal, and to kick things off I’m going to tell you what my favourite animal is!

ARE YOU READY?!

Drum roll, please…

PENGUINS!

As long as I can remember I have love penguins! But it was only after this week’s lecture that, I realised my love for these animals could be drawn from the fact that they are often represented like humans or having human-like qualities, otherwise known as anthropomorphism.

Anthropomorphism – is the term uses when we give “human characteristics to animals, inanimate objects or natural phenomena” (Nauert, 2015).

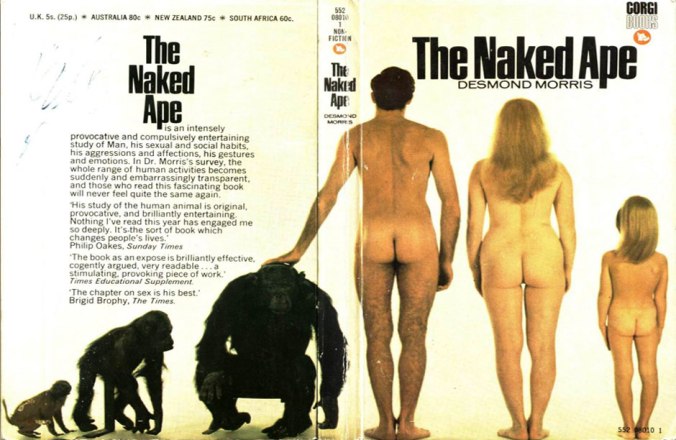

Desmond Morris a zoologist conducted a study on more that 80,000 British school children, asking them what their favourite animals are and why. The results Morris found, highlight the heavy impact anthropomorphism is having on our minds.

His results found that the most common animals which were favoured were ones that had hair, could stand on two legs or could be trained to stand on two legs and/or tricks; chimpanzees, bears, pandas, giraffes and dogs were the most common animals in this grouping. Though birds were not highly viewed in this survey, there was one particular one that caught me eye, this particular bird was able to stand much like a human and at the right angle looked to be wearing a tux…take a wild guess and what bird it was?

A penguin!

I have never thought of penguins having human-like qualities before, however, after watching ‘March of the Penguins’ (2005), I started to understand how human traits were connected to my tuxedo-clad friends. Religious groups associated Penguins with monogamy and the perfect nuclear family, deeming the film as “proof” of intelligent design, thus promoting the documentary’s anthropomorphism further.

However, “some scientists are criticising the movie March of the Penguins for portraying the Antarctic seabirds almost as tiny, two-tone humans” (Mayell, 2005). The emperor penguins are seen making their journey across the cold Antarctic floors in “a quest to find the perfect mate and start a family against impossible odds.” The narration performed by Morgan Freeman provides us with more emphasis of humanisation, “‘[the penguins] are not that different from us, really. They pout, they bellow, they strut, and occasionally they will engage in some contact sports.” It is from language amongst camera techniques and editing that have given this particular documentary the Disney model. Margaret King states that the Disney model is selective of the perception of animal life and is exploited for human desire to find patterns in the natural world that are similar to our own. She further explains, “by subjectifying the animals, the Disney format creates audience identification with animal “stars” and arouses empathy with the affinity for their situations.” The continuation of these elements to emphasis human desire is pressed on firmly throughout the documentary, creating a narrative in which nature is redefined. “Nature, but a very special kind: not an ecosystem, but an ego-system – one viewed through a self-referential human lens: anthropomorphised, sentimentalised and moralised.”

One the other hand you have countless scientists who believe much like the film, anthropomorphism isn’t a negative thing but can be an upside to understanding animals and the start of building a relationship with them. Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal argues that anthropomorphism is the unwillingness to recognise the human-like traits of animals or what he refers to as “anthropodenial”. De Waal’s phenomenon is closely linked to those made by people in the fifteenth century, which saw dogs, pigs and other domesticated animals put on trial for crimes, like any other human being. Within the nineteenth century and to the present day, many naturalists have sought out the connections between animals and human intelligence. This may be odd and completely absurd but this mindset is what we can see now in regards to our views for animals whether they are wild or domesticated. We seem to have forgotten that animals are animals and it is in their nature to have animal’s instincts and be unpredictable with their behaviour.

Research has convinced us that animal’s intelligence is either the same, close to or of a higher level of intelligence than that of humans. However, research doesn’t tell you why these tests are conclusive. Many of these tests fail because the animals are not in the environments they thrive in, they have been tortured by the refusal of food, and because their “intelligence” cannot be described to our level of understanding. This misconception of animal’s intelligence and the opposite of anthropomorphism have led to many incidents at zoo’s, aquarium’s and at the infamous Sea World, Florida with an Orca killing its trainer.

In spite of all the incidences of injury and death, all such claims have been dismissed and covered with the notion of anthropomorphism, that is wasn’t the fault of the animal but of the human in contact with it.

When will we truly understand that animals are animals and there is a distinct line that separates the different species from one another because they are not the same?

References:

Leane, E & Pfennigwerth, S 2011, Marching on Thin Ice: The Politics of Penguin Films. In: Considering Animals: Contemporary Case Studies in Human-Animal Relations, Ashgate, Farnham, Surrey, pp. 29-40 <http://eprints.utas.edu.au/17344/>

Mayell, H 2005, “March of the Penguins” Too Lovey-Dovey to Be True?, National Geographic, weblog, 19 August, viewed 22 March 2017, <http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2005/08/0819_050819_march_penguins.html>

Nauert, D 2015, Why Do We Anthropomorphise?, Psych Central, weblog post, viewed 22 March 2017, <https://psychcentral.com/news/2010/03/01/why-do-we-anthropomorphize/11766.html>

Riederer, R 2016, Inky The Octopus And The Upside Of Anthropomorphism, The New Yorker, weblog post, 26 April, viewed 23 March 2017, <http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/inky-the-octopus-and-the-upsides-of-anthropomorphism>

Russo, C 2013, Wildlife documentaries or dramatic science?, PLOS, weblog, 4 February, viewed 23 March 2017, <http://blogs.plos.org/scied/2013/02/04/wildlife-documentaries-or-dramatic-science/>